The Heritage and Historical Legacy of Bihar

Bihar stands as one of the most historically significant regions in the world, a land where human civilization reached extraordinary heights in philosophy, education, governance, and arts thousands of years ago. The state's heritage encompasses millennia of cultural evolution, from the prehistoric settlements along the Ganges river to the mighty empires that shaped the course of South Asian history. This ancient land witnessed the birth of two major world religions, housed the world's first residential university, and served as the political center for some of India's most powerful dynasties. Understanding Bihar's heritage means understanding the very foundations of Indian civilization and its profound contributions to global culture and knowledge.

The archaeological and architectural treasures scattered across Bihar provide tangible connections to this illustrious past. Every brick structure, every carved stone pillar, every ancient manuscript fragment tells a story of human achievement, spiritual seeking, and intellectual curiosity. These heritage sites are not mere tourist attractions; they are classrooms without walls where history comes alive, where ancient wisdom speaks to modern minds, and where the continuity of human civilization becomes evident. The preservation and presentation of these sites represent an ongoing commitment to honoring the past while making it accessible and relevant to present and future generations.

Bihar's designation of multiple UNESCO World Heritage Sites and numerous sites on the tentative list reflects the international recognition of its cultural significance. Organizations like the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), UNESCO, and various international cultural preservation bodies work continuously to protect, restore, and study Bihar's heritage. These collaborative efforts involve cutting-edge archaeological techniques, conservation science, and community engagement to ensure that Bihar's heritage remains intact and interpretable for centuries to come. The challenge lies in balancing preservation needs with tourism development and local community requirements, a task that requires careful planning and sustained commitment.

Nalanda University: Ancient Seat of Learning

Nalanda University, located approximately 95 kilometers southeast of Patna, represents one of humanity's greatest educational achievements and stands as a powerful symbol of ancient India's intellectual prowess. Founded in the 5th century CE during the Gupta dynasty, Nalanda evolved into an international center of learning that operated continuously for nearly 800 years until its destruction in the 12th century. At its zenith, this extraordinary institution attracted over 10,000 students and 2,000 teachers from across Asia, including present-day China, Korea, Japan, Tibet, Mongolia, Turkey, Sri Lanka, and Southeast Asia. The university offered comprehensive education in Buddhist philosophy, logic, grammar, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, and numerous other disciplines, making it the ancient world's equivalent of modern multidisciplinary universities.

The architectural magnificence of Nalanda, evident even in its ruined state, speaks to the sophistication and scale of this ancient university. The excavated remains reveal a meticulously planned campus spread over an area of approximately 14 hectares, though scholars believe the original campus was far more extensive. The complex includes eleven monasteries and six major temple structures arranged in an organized layout that facilitated academic activities, residential life, and spiritual practices. The monasteries, constructed in red brick with stone foundations, featured individual cells for students arranged around central courtyards, providing a conducive environment for study and meditation.

The teaching methodology at Nalanda combined rigorous intellectual discourse, debate, and practical application, creating an environment where critical thinking and analytical skills were paramount. Admission to Nalanda was highly competitive, with only about 20-30% of applicants being accepted after rigorous entrance examinations conducted by learned gatekeepers. The curriculum included preliminary education in grammar and logic, followed by specialized studies in chosen fields under the guidance of renowned scholars. The emphasis on debate as a pedagogical tool meant that students developed not just knowledge but also the ability to articulate, defend, and refine their ideas through intellectual combat.

The legendary library of Nalanda, known as Dharma Gunj (Mountain of Truth), was housed in three multi-story buildings called Ratnasagar, Ratnodadhi, and Ratnaranjak. This library was one of the most extensive collections of manuscripts and texts in the ancient world, containing hundreds of thousands of volumes on every conceivable subject. When the university was destroyed by invaders in 1193 CE, the library reportedly burned for three months, representing an incalculable loss to human knowledge. Many texts that survived, carried away by fleeing scholars to Tibet and other regions, formed the foundation of Buddhist literary traditions in those areas.

The destruction of Nalanda marked a tragic turning point in Indian educational history, but its legacy endured through the teachings of scholars who studied there and the institutions they established elsewhere. The Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang, who studied at Nalanda in the 7th century, left detailed accounts of the university in his writings, providing invaluable historical information about its operations, curriculum, and scholarly environment. His descriptions helped archaeologists identify and excavate the site in the 19th and 20th centuries, revealing the physical remains of this great institution to the modern world.

Today, Nalanda stands as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, attracting scholars, archaeologists, tourists, and pilgrims who come to pay homage to this temple of learning. The site museum displays numerous artifacts recovered during excavations, including Buddhist and Hindu sculptures, seals, coins, pottery, and architectural fragments that provide insights into daily life at the ancient university. Recent years have seen the establishment of a new Nalanda University nearby, an international institution envisioned as a revival of the ancient university's spirit and mission, once again making Nalanda a center of learning and cross-cultural exchange.

Nalanda University Facts

- Operational for approximately 800 years (427-1197 CE)

- Covered area: 14+ hectares (excavated portion)

- Peak enrollment: 10,000+ students from across Asia

- Faculty: 2,000+ scholars and teachers

- Library: 9 million manuscripts (estimated)

- UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2016

Vikramashila: The Other Great Buddhist University

While Nalanda often receives primary attention, Vikramashila University, established by King Dharmapala of the Pala dynasty in the late 8th century CE, played an equally crucial role in the development and propagation of Buddhism, particularly Vajrayana Buddhism. Located in the Bhagalpur district of Bihar, Vikramashila functioned as the sister institution to Nalanda and eventually surpassed it in importance during the later Pala period. The university specialized in tantric Buddhism and became the primary center for the study and practice of Vajrayana teachings, attracting scholars particularly from Tibet, where this form of Buddhism became dominant.

The architectural layout of Vikramashila, revealed through systematic excavations by the Archaeological Survey of India, demonstrates sophisticated planning and religious symbolism. The main stupa, located at the center of the complex, follows a cruciform design with elaborately decorated entrances facing the cardinal directions. Each entrance was guarded by a renowned scholar who examined candidates seeking admission, a practice that ensured high academic standards. The arrangement of monasteries, libraries, and teaching spaces around the central stupa created both a functional campus and a three-dimensional mandala, reflecting Buddhist cosmological concepts in physical form.

Vikramashila's faculty included some of the most distinguished Buddhist scholars of the medieval period, including Atisha Dipankara, who later traveled to Tibet and played a pivotal role in the revival of Buddhism there. The university's systematic approach to tantric studies, with carefully structured stages of initiation and practice, influenced Buddhist traditions across the Himalayan region. Vikramashila also maintained close connections with other Buddhist centers of learning, creating a network of scholarly exchange that facilitated the spread of Buddhist ideas and practices throughout Asia.

The destruction of Vikramashila occurred around the same time as Nalanda's fall, marking the end of institutional Buddhism's dominance in eastern India. However, its influence continued through the students and teachers who carried its teachings to other regions. The excavated site today offers visitors a glimpse into the physical remains of this great institution, with the main stupa, monastery foundations, and numerous artistic fragments providing evidence of its former glory. The site museum displays sculptural pieces, seals, and other artifacts that illustrate the university's religious and educational functions.

Barabar Caves: India's Oldest Rock-Cut Architecture

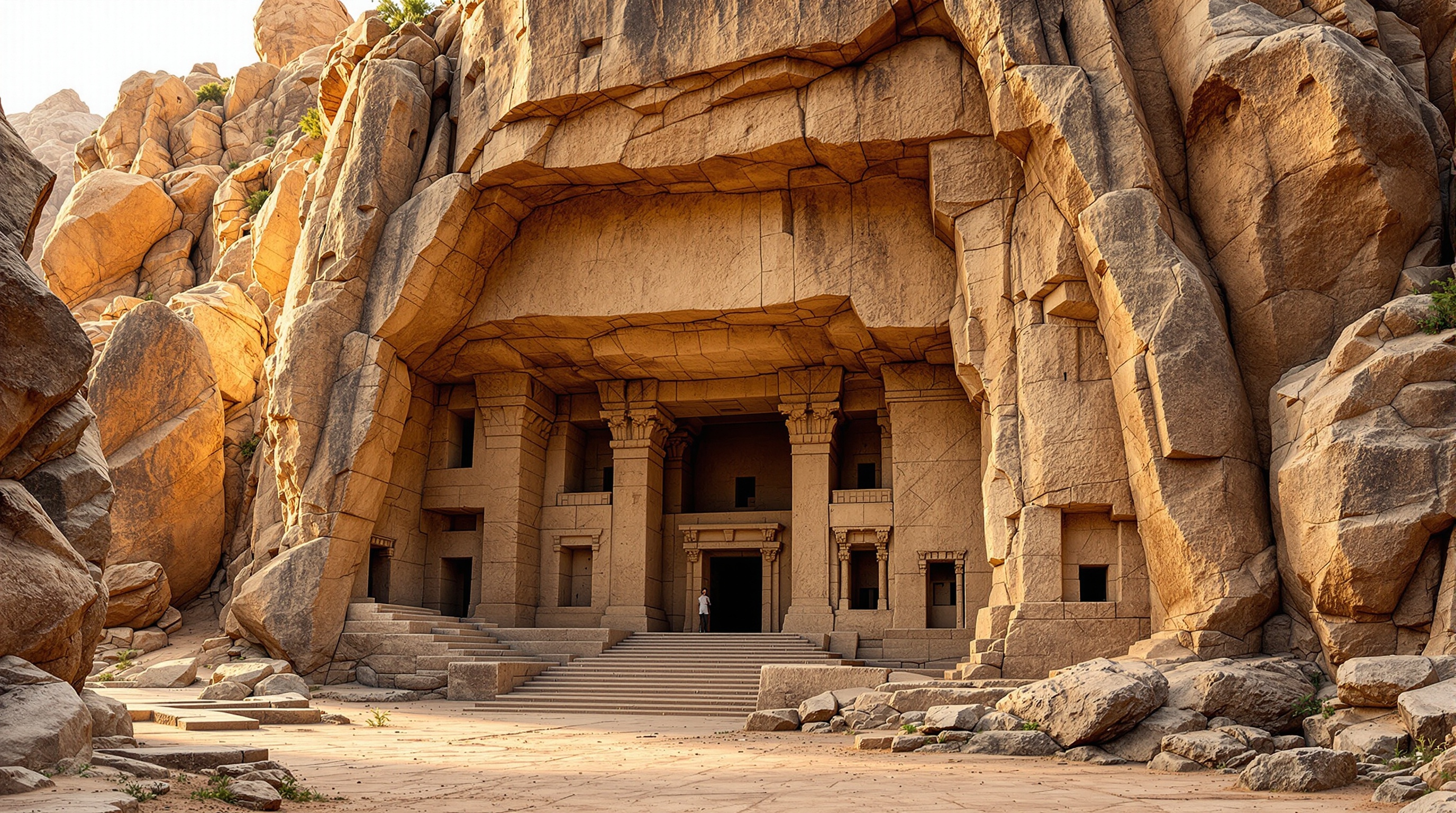

The Barabar Caves, located approximately 35 kilometers north of Gaya in the Jehanabad district, represent the oldest surviving examples of rock-cut architecture in India, predating similar caves at Ajanta, Ellora, and Elephanta by several centuries. Dating to the Mauryan period (322-185 BCE), these caves were carved during the reigns of Emperors Ashoka and his grandson Dasharatha, as evidenced by inscriptions found within them. The caves served as monastic retreats for the Ajivika sect, a religious movement contemporary to Buddhism and Jainism that emphasized strict asceticism and determinism.

The technical sophistication demonstrated in the Barabar Caves remains impressive even by modern standards. The caves were carved into extremely hard granite rock using only primitive tools, yet their interiors display a mirror-like polish that gives the rock surfaces a glass-like quality. This polish, achieved through unknown techniques, has survived for over two millennia and continues to puzzle archaeologists and engineers. The acoustic properties of the caves are equally remarkable, with some chambers producing echoing effects that suggest they may have been designed for meditation practices or ritualistic chanting.

The Barabar group includes four main caves: Lomas Rishi, Sudama, Karan Chaupar, and Visvakarma. Lomas Rishi cave features the most elaborate entrance, with a horseshoe-shaped arch (chaitya) decorated with carved elephants proceeding toward stupas, representing one of the earliest examples of this architectural motif that became standard in later Buddhist cave architecture. The Sudama cave contains two chambers connected by a passage, with inscriptions dedicated by Emperor Ashoka for the use of Ajivika monks. These inscriptions are among the oldest examples of Brahmi script, providing valuable linguistic and historical information.

The nearby Nagarjuni hills contain three additional caves (Nagarjuni, Gopika, and Vadathika) that show similar characteristics and Dasharatha's inscriptions, expanding the cave complex and demonstrating continued royal patronage across generations. The caves' remote location, surrounded by rocky outcrops and natural beauty, creates an atmosphere conducive to contemplation and spiritual practice, helping visitors understand why ancient ascetics chose these sites for their retreats. The caves have been declared national heritage monuments and are maintained by the Archaeological Survey of India, though they remain relatively less visited compared to other Bihar heritage sites, offering a more tranquil experience for those who make the journey.

Pataliputra: Ancient Imperial Capital

Ancient Pataliputra, modern Patna, served as one of the most important political centers in ancient India for over a thousand years. Founded in the 5th century BCE by King Ajatashatru of the Haryanka dynasty, Pataliputra reached its zenith as the capital of the Mauryan Empire (322-185 BCE) and later the Gupta Empire (320-550 CE). During these periods, Pataliputra was one of the largest and most prosperous cities in the world, with contemporary accounts describing it as a magnificent metropolis with sophisticated urban planning, formidable fortifications, and splendid palaces.

The Greek ambassador Megasthenes, who visited Pataliputra during Chandragupta Maurya's reign, left detailed descriptions of the city in his work "Indica." He described a city extending along the Ganges river for approximately 14 kilometers with a width of 3 kilometers, protected by a massive wooden palisade with 64 gates and 570 watchtowers. The city featured wide roads, sophisticated drainage systems, public buildings, parks, and a magnificent palace that Megasthenes compared favorably to the Persian palaces at Susa and Ecbatana. Archaeological excavations in the 20th century confirmed many of these descriptions, uncovering remains of the wooden palisade, pillared halls, and various urban structures.

The Mauryan period represented Pataliputra's golden age when Emperor Ashoka ruled from this capital after his conversion to Buddhism following the bloody Kalinga War. Under Ashoka's patronage, Buddhism flourished, and Pataliputra became a center of Buddhist scholarship and missionary activities. The Third Buddhist Council, held in Pataliputra around 250 BCE under Ashoka's sponsorship, codified Buddhist teachings and dispatched missions to spread Buddhism across Asia. The city's cosmopolitan character, with merchants, scholars, and diplomats from various regions, made it a true international metropolis where different cultures, languages, and ideas intersected.

The Gupta period witnessed a renaissance of arts, sciences, and culture in Pataliputra. This era produced remarkable achievements in mathematics (including the concept of zero), astronomy, literature, philosophy, and arts. The famous playwright Kalidasa and the astronomer-mathematician Aryabhata were associated with the Gupta court at Pataliputra, contributing to the period often called the "Golden Age of India." The city continued as an important center even after the Gupta Empire's decline, maintaining its significance through various dynasties until the capital shifted to other locations in medieval times.

Modern Patna still contains numerous archaeological sites and museums that showcase its ancient heritage. The Patna Museum houses an impressive collection of artifacts from the Mauryan and Gupta periods, including the famous Didarganj Yakshi sculpture, considered one of the finest examples of Mauryan art. The Kumhrar excavation site, located within the city, displays remains of the Mauryan palace's pillared hall (arogya vihar), providing tangible connections to the city's ancient glory. Recent archaeological work continues to uncover new evidence of Pataliputra's urban character and historical importance.

Vaishali: The World's First Republic

Vaishali, located approximately 55 kilometers north of Patna, holds a unique place in world history as potentially the world's first republic or democratic state. Around the 6th century BCE, when monarchies dominated political structures globally, Vaishali was governed by the Vajjian confederacy, a republican system where power was shared among elected representatives from eight clans. This early form of democratic governance, known as "Gana-Sangha" (republic), demonstrates that republican principles existed in India long before similar systems developed in ancient Greece or Rome.

The city's political significance is matched by its religious importance. Lord Mahavira, the 24th and last Tirthankara of Jainism, was born in Vaishali around 599 BCE, making it one of the holiest sites in Jainism. Buddha visited Vaishali multiple times and delivered his last sermon here before attaining Mahaparinirvana. The Second Buddhist Council was held in Vaishali approximately 100 years after Buddha's death to address disputes regarding monastic discipline. These religious connections, combined with its political innovations, make Vaishali a site of extraordinary historical and cultural significance.

The Ashoka Pillar at Vaishali stands as one of the best-preserved examples of Mauryan architectural and sculptural excellence. This 18.3-meter-high pillar, crowned with a life-size lion figure facing north (the direction Buddha took on his last journey), marks the spot where Buddha supposedly predicted his approaching death. The single-piece sandstone pillar, brought from quarries in Chunar near Varanasi, demonstrates the logistical capabilities and artistic achievements of the Mauryan Empire. Unlike many other Ashoka pillars that were moved or damaged over centuries, the Vaishali pillar remains in its original location, maintaining its connection to the historical events it commemorates.

Archaeological excavations at Vaishali have revealed remains of stupas, monasteries, and urban structures dating to various periods. The Vishwa Shanti Stupa (World Peace Pagoda), a modern addition built by Japanese Buddhists in 1996, houses relics of Buddha and offers panoramic views of the ancient city's landscape. The nearby Abhishek Pushkarini (Coronation Tank), an ancient water reservoir where republican leaders were consecrated, still exists and receives Buddhist pilgrims who believe that Buddha bathed here during his visits. The Kutagarasala Vihara, an ancient monastery where Buddha stayed during his visits, has been excavated and marked, allowing visitors to walk the same grounds that Buddha once tread.

Kesariya Stupa: The Tallest Buddhist Monument

The Kesariya Stupa, located in the East Champaran district about 110 kilometers from Patna, represents one of Bihar's most impressive yet lesser-known archaeological treasures. At approximately 104 feet in height with a circumference of nearly 1,400 feet at its base, Kesariya is believed to be the tallest Buddhist stupa in the world, even taller than the famous Borobudur in Indonesia. The stupa's construction dates to the 3rd century BCE during Emperor Ashoka's reign, though it underwent additions and modifications during subsequent periods, particularly under the Gupta and Pala dynasties.

The stupa's historical significance is enhanced by its association with Buddha's final journey. Buddhist texts mention that Buddha spent some time in Kesariya during his last voyage from Rajgir to Kushinagar (where he attained Mahaparinirvana). The local Licchavis, who had accompanied Buddha from Vaishali, were reluctant to leave him, prompting Buddha to give them his alms bowl as a memento. Ashoka later built this massive stupa to commemorate this event and possibly to enshrine Buddha's relics.

The stupa's architectural design follows a unique terraced circular structure with multiple levels, each decorated with numerous Buddha statues and stupas. Excavations have revealed five circular terraces one above the other, creating a stepped pyramid effect typical of late Buddhist architecture. The statues of Buddha in various mudras (hand gestures) are carved in niches around each terrace, originally numbering in the hundreds, though many have been damaged or removed over centuries. The artistic style of the sculptures provides valuable insights into the evolution of Buddhist iconography and regional artistic traditions from the Mauryan through the Pala periods.

For centuries, the stupa was buried under a large earthen mound that locals called "Devraha Baba ki Dih" (the mound of the ancient sage). Its actual character as a Buddhist stupa was only discovered during archaeological surveys in the early 20th century, and systematic excavations began in 1998. The ongoing excavation and conservation work continues to reveal new aspects of this monument's structure and history. Despite its archaeological significance and impressive size, Kesariya remains relatively unvisited compared to other Buddhist sites, offering travelers a more authentic and less commercialized experience of Bihar's Buddhist heritage.

🏛️ Nalanda University

UNESCO World Heritage Site - Ancient international university (5th-12th century CE)

⛰️ Barabar Caves

India's oldest rock-cut caves from Mauryan period with mirror-polished interiors

🏛️ Vikramashila

Major Buddhist tantric university, sister institution to Nalanda

🏛️ Kesariya Stupa

World's tallest Buddhist stupa at 104 feet, built by Emperor Ashoka

Sasaram: Sher Shah Suri's Architectural Legacy

Sasaram, located in the Rohtas district of Bihar, houses one of India's finest examples of Indo-Islamic architecture in the tomb of Sher Shah Suri, the Afghan ruler who briefly but significantly interrupted Mughal rule in the 16th century. Sher Shah Suri, who ruled from 1540 to 1545 CE, was not only a formidable military leader but also an excellent administrator who introduced numerous reforms that influenced governance in the Indian subcontinent for centuries. His tomb at Sasaram stands as a testament to his architectural vision and represents the zenith of pre-Mughal Afghan architecture in India.

The tomb, completed in 1545 CE shortly after Sher Shah's death, is a magnificent red sandstone structure set in the middle of an artificial lake, creating a stunning reflection effect that enhances its architectural beauty. The five-story octagonal structure stands approximately 122 feet high and features a massive dome surrounded by eight smaller domed kiosks (chhatris) at the corners. The architectural design shows influences from Lodi and early Mughal styles while maintaining distinctive Afghan elements, creating a transitional style that bridges different architectural traditions. The tomb is considered an architectural precursor to the famous Taj Mahal, sharing certain design principles and aesthetic approaches.

The tomb complex includes several other structures, including the tomb of Sher Shah's father Hassan Khan Sur and his son Islam Shah, though neither matches the grandeur of Sher Shah's monument. The careful urban planning evident in the tomb's placement, causeway connections, and surrounding landscape demonstrates the sophisticated architectural thinking of the period. The use of red sandstone, intricate jali (lattice) work, calligraphic inscriptions, and structural engineering showcases the high level of craftsmanship available to Sher Shah's builders.

Beyond the tomb, Sasaram contains the ruins of Rohtasgarh Fort, an ancient fortification perched on a hilltop that served as a strategic military installation for various dynasties. The fort's massive walls, extending over several kilometers, enclose numerous structures including palaces, temples, mosques, and water reservoirs. The fort has witnessed the rule of Mauryans, Guptas, Rajputs, Afghans, and Mughals, with each leaving their architectural signatures. The combination of natural defensive advantages and human-made fortifications makes Rohtasgarh one of the most formidable forts in eastern India.

Archaeological Museums: Preserving Bihar's Heritage

Bihar's heritage is not just preserved in monuments and archaeological sites but also in various museums across the state that house invaluable collections of artifacts, sculptures, manuscripts, and other cultural objects. The Patna Museum, established in 1917, serves as the state's premier museum with collections spanning from prehistoric times to the modern period. The museum's Mauryan gallery displays the famous Didarganj Yakshi, a highly polished sandstone sculpture that exemplifies Mauryan artistic excellence and has become an icon of ancient Indian art. Other significant exhibits include Buddha's ashes kept in a casket, Gupta period sculptures, Mughal and Rajput paintings, and natural history specimens.

The Nalanda Archaeological Museum, located near the ancient university ruins, specializes in artifacts recovered from the site during excavations. The museum displays Buddhist and Hindu sculptures, architectural fragments, seals, coins, and pottery that provide insights into daily life at the ancient university. Particularly significant are the numerous Buddha images in different postures and mudras, representing various Buddhist schools and artistic traditions from across Asia. The museum also houses copper plate inscriptions, palm leaf manuscripts, and other documentary materials that help scholars understand the university's administrative systems and curricular content.

The Bihar Museum in Patna, opened in 2015, represents a modern approach to museum management and heritage presentation. This state-of-the-art facility uses contemporary display techniques, multimedia presentations, and interactive exhibits to make Bihar's heritage accessible and engaging for diverse audiences. The museum includes galleries on Bihar's history, art, textiles, and natural environment, presenting comprehensive narratives about the state's cultural evolution. Special exhibitions on themes like the Buddhist heritage, Mauryan period, and contemporary art provide focused explorations of specific aspects of Bihar's cultural landscape.

Smaller regional museums in Vaishali, Rajgir, and other heritage sites offer localized collections that complement the major museums. These institutions often work in collaboration with archaeological departments and universities, serving not just as display spaces but also as research centers where scholars study artifacts and manuscripts. The digitization of museum collections and creation of online databases are making Bihar's heritage accessible to global audiences, supporting research and education while promoting cultural tourism. Conservation laboratories attached to major museums work on preserving fragile artifacts, applying scientific methods to protect Bihar's material heritage for future generations.

Conservation Challenges and Efforts

Preserving Bihar's extensive heritage faces numerous challenges ranging from environmental factors to human pressures. Many ancient monuments constructed with brick and stone suffer from weathering, erosion, vegetation growth, and water seepage that gradually deteriorate structural integrity. The red bricks used in Nalanda and Vikramashila, though remarkably durable, are vulnerable to moisture and require continuous maintenance. The Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) implements various conservation techniques including chemical treatments, structural stabilization, vegetation removal, and drainage improvements to protect these monuments from natural deterioration.

Tourism pressure represents another significant challenge, particularly at major sites like Bodh Gaya and Nalanda where visitor numbers have increased dramatically. High footfall causes wear on ancient structures, while inadequate waste management and lack of visitor education sometimes lead to site degradation. Balancing tourism development with heritage conservation requires carefully planned visitor management strategies including designated pathways, visitor limits, guided tours, and strict enforcement of rules regarding touching artifacts or monuments. The installation of interpretation centers and museums helps channel visitors into controlled environments while reducing pressure on fragile archaeological remains.

Funding limitations often constrain conservation and archaeological work despite Bihar's heritage significance. Government allocations for heritage conservation, though substantial, are insufficient given the vast number of sites requiring attention. International collaborations with UNESCO, foreign archaeological institutes, and cultural organizations help supplement resources and bring technical expertise. Recent years have seen increased private sector involvement through corporate social responsibility initiatives and heritage adoption programs where companies sponsor conservation work at specific monuments.

Community engagement in heritage conservation has emerged as a crucial strategy for sustainable preservation. Local communities living near heritage sites often possess traditional knowledge about monuments and can serve as custodians if properly trained and incentivized. Heritage awareness programs in schools, community workshops, and local festivals help build appreciation for cultural heritage among new generations. Initiatives that link heritage conservation with livelihood opportunities through tourism services, handicraft production, and cultural performances create stakeholder interest in preservation, transforming local communities from passive observers to active heritage protectors.

Future of Bihar's Heritage Tourism

The future of Bihar's heritage tourism looks promising with several initiatives aimed at improving infrastructure, visitor experiences, and conservation standards. The development of the Buddhist Circuit as an integrated tourism product involves coordinated efforts across multiple states and even neighboring countries. Improved transportation connectivity, including dedicated tourist circuits, enhanced railway services, and better road infrastructure, is making heritage sites more accessible. The proposal for a luxury tourist train focused on the Buddhist circuit would provide high-end tourists with comfortable access to multiple sites while generating revenues that could support conservation efforts.

Digital technology offers exciting possibilities for heritage presentation and interpretation. Virtual reality experiences that recreate ancient Nalanda or Pataliputra in their prime can provide visitors with immersive historical experiences that complement physical site visits. Augmented reality applications allowing smartphone users to see reconstructed buildings superimposed on current ruins help bridge the gap between present appearance and historical reality. Online virtual tours make Bihar's heritage accessible to global audiences who cannot physically visit, promoting awareness and appreciation while potentially inspiring future visits.

Academic tourism represents an under-explored opportunity for Bihar given its educational heritage. Developing programs that allow students, researchers, and scholars to spend extended periods studying at heritage sites could generate sustainable tourism revenues while advancing academic research. The revival of Nalanda University as an international institution creates possibilities for academic tourism that combines contemporary education with heritage experiences. Similar programs could be developed around other themes like ancient architecture, Buddhist studies, or archaeological methods, positioning Bihar as a destination for educational tourism.

Climate change poses emerging threats to heritage conservation requiring proactive adaptive strategies. Increased rainfall intensity, flooding, temperature variations, and extreme weather events can accelerate monument deterioration. Developing climate-resilient conservation approaches, improving drainage systems, and implementing early warning systems for extreme weather are essential for protecting Bihar's heritage. Research on traditional building materials and techniques may offer sustainable solutions that are both effective and culturally appropriate. International cooperation on climate adaptation for heritage sites can bring resources and expertise to address these complex challenges.

Conclusion: Heritage as Living Legacy

Bihar's heritage is not merely a collection of old buildings and artifacts but a living legacy that continues to inspire, educate, and connect people across time and space. The monuments and sites scattered across the state represent thousands of years of human creativity, spiritual seeking, intellectual inquiry, and artistic expression. They embody values of learning, peace, tolerance, and excellence that remain relevant in contemporary times. Visiting these heritage sites offers not just aesthetic pleasure or historical knowledge but profound experiences that can transform understanding of human potential and cultural continuity.

The responsibility of preserving and presenting this heritage belongs not just to government agencies or heritage professionals but to all of us who value human history and cultural diversity. Every visitor to Bihar's heritage sites can contribute to conservation by practicing responsible tourism, supporting local communities, and spreading awareness about Bihar's cultural significance. Schools and educational institutions can incorporate Bihar's heritage into curricula, helping young people develop appreciation for their cultural roots. Media, artists, and content creators can tell Bihar's heritage stories in engaging ways that reach broader audiences.

As Bihar continues its development journey, the challenge lies in integrating heritage conservation with modernization aspirations. Heritage sites should not be isolated museums disconnected from contemporary life but integrated into urban planning, economic development, and social progress. The wisdom embedded in ancient educational systems, governance models, and cultural practices can inform modern approaches to persistent challenges. By studying how ancient Bihar created inclusive institutions like Nalanda and Vaishali's republic, we might find inspiration for building more equitable and enlightened societies today. Bihar's heritage, properly understood and preserved, thus becomes not just a window to the past but a guide for the future.